As part of the Knowledge Resistance project, a conference was organised in Stockholm from 23rd to 25th August 2022 to bring together philosophers, psychologists, media studies researchers, and journalists and discuss recent work on misinformation. This event was organised by Åsa Wikforss (interviewed on knowledge resistance here).

|

| Stockholm University, Albano |

In this report, I will summarise some of the talks.

DAY 1

In his talk entitled “Resistance to Knowledge and Vulnerability to Deception”, Christopher F. Chabris (Geisinger Health System) argued that we need to understand our vulnerabilities to deception in order to appreciate the social aspects of knowledge resistance. He illustrated with many interesting examples of famous deceptions and frauds how deceivers exploit blind spots in our attention and some of our cognitive habits.

|

| Christopher Chabris |

For instance, we tend to judge something as accurate if it is predictable and consistent. We make predictions all the time about what will happen and don’t question things unless our expectations are not met. Deceivers take advantage of this and, when they commit fraud, they make sure they meet our expectations. Another habit we have consists in questioning positions that are not consistent, and we tend not to like people who change their minds (e.g. politicians who change their views on policy issues). Deceivers present their views as consistent to lower our defences.

Another interesting finding is that we trust someone more if we feel we recognise them even when the recognition is illusory: maybe their names sound familiar to us or we can associate them with individuals or organisations that we know and respect. This feature is exploited by fraudsters who make sure they are associated with famous people or create fake organisations with authoritatively sounding names that resemble the names of genuine organisations. We also like explanations that are simple, precise, and told with confidence. Deceivers always exude confidence.

Leor Zmigrod (University of Cambridge) presented a talk entitled “Political Misinformation and Disinformation as Cognitive Inference Problems”. She asked how ideologies colour our understanding of the world, thinking about ideologies as compelling stories that describe and prescribe (e.g., racism, veganism, nationalism, religious fundamentalism).

Zmigrod studied two important dimensions of ideologies in her empirical research: how rigidly we uphold the dogma and how antagonistic we feel to ideologically different people. The rigidity is strongly related to dogmatism and knowledge resistance. The antagonism has at its extreme cases of violence motivated by differences in ideology.

|

| Leor Zmigrod |

What makes some people believe ideologies more fervently, be more extreme in their endorsement of their ideologies? The results paint a complex picture. Cognitive rigidity predicts more extremist ideologies, independent whether the person is at the right or at the left of the political spectrum. Intelligence and intellectual humility both turn out to be routes to flexibility, although either is sufficient to ensure flexibility without the other.

Emotional dysregulation (impulsivity), risk taking, executive dysfunction, and perceptual impairments all characterise extremism in ideologies. Zmigrod presented several findings where people with more dogmatic views showed not only lack of flexibility in a variety of tasks but also difficulties in perceptual tasks. She also considered how dogmatic individuals are slower at integrating evidence but make decisions faster, which means that they often act prematurely—before they have the evidence they need.

DAY 2

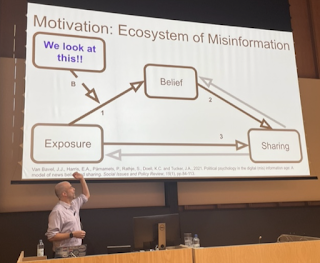

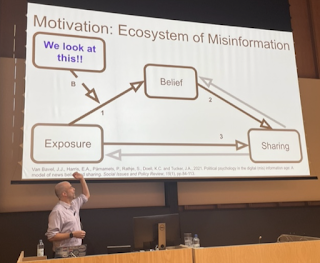

Joshua Tucker (New York University) presented a talk entitled “Do Your Own Research? How Searching Online to Evaluate Misinformation Can Increase Belief that it is True”. The aim of the research is to evaluate a common tip offered in digital media literacy courses: when encountering a piece of information that we suspect it may be misleading, we should use a search engine to verify that piece of information. This tip is problematic because we do not know what effects searching for a piece of information online (using search engines) has on our belief in the piece of information. The issue is that by searching online for that content we end up with unreliable sources only—because mainstream news outlets do not report fake news and so search engines return low-quality information.

|

| Joshua Tucker |

With true information, the return of unreliable sources from research engines is minimal (around 10%). But with false information, the return of unreliable sources from research engines is much greater (around 30%). Which means that when searching online, people are more easily exposed to unreliable sources especially when they are looking for news that are misleading and fake. But are there any individual differences in this phenomenon? Who is most exposed to low-quality information? The answer is older people (not necessarily people who ideological views are congruent with the misleading information and not necessarily people who lack digital literacy).

Another interesting result is that low-quality information is more likely to be returned if we use the headline of the original story or the URL to search for more sources. That's because people who have an interest in spreading fake news "copy and paste" the same content and make it available in several places. A suggestion is that it is not the act of searching itself but the exposure to low-quality sources that makes it more likely that we end up believing the misleading information we did the search on.

Kathrin Glüer presented her take on the relationship between bad beliefs and rationality in the talk "Rationality and Bad Beliefs", focusing on Neil Levy's recent book. According to Glüer, for Levy it is the input to the process of belief formation that is problematic not the process itself. Rational processes tend to get things right and take inputs that are genuine epistemic reasons for their outputs. But the input may come from unreliable sources. How do lay people evaluate the reliability of the sources?

|

| Kathrin Glüer |

People follow social cues of epistemic authority, encompassing competence and benevolence. They tend to trust members of their in-group and mistrust members of out-groups. According to Levy, this is an understandable and even rational choice, because we take members of our group to be competent and benevolent. But when cues of epistemic authority are misleading, then the input leads to the formation of bad beliefs. Glüer raised some concerns about the strong claim that the processes responsible for bad beliefs are "wholly rational" as Levy stated, and about the role of benevolence in judgements about sources of reliability.

Tobias Granwald and

Andreas Olsson (Karolinska Institute) presented a paper entitled “Conformity and partisanship impact perceived truthfulness, liking, and sharing of tweets". What determines whether the tweet is something that we want to share and like and whether it affects our behaviour? In the study researchers asked participants to rate the truthfulness of a news tweet and in one conditions participants are also shown how many people liked the tweet.

When participants rated a tweet as truthful they were more likely to like it and share it. When participants saw the tweet being liked and shared by others, they were more likely to like it and share it--this effect is bigger if the people liking and retweeting the tweet are from your in-group. Strength of identity does not seem to affect liking or sharing. One interesting question is whether the results will be the same when the selected tweets are more controversial and highly partisan--this will be investigated in future studies.

Kevin Dorst (University of Pittsburgh) asked “What's Puzzling about Polarization?” First, he reviewed a number of features of polarisation that we may think of as problematic (such as deep disagreement) that are not actually reasons to believe that polarisation is irrational. People have different views because they have access to different information and they preserve their own views even after talking to each other because the evidence for their positions is still different. When they are exposed to the same evidence, they may interpret it differently due to their background assumptions.

|

| Kevin Dorst |

What Dorst find puzzling about polarisation is its self-predictability which forces us to choose between two options: either self-predictability is not irrational, or we should embrace political agnosticism and have no political beliefs at all! How does self-predictability raises a puzzle for polarisation? When we predict which beliefs we will have in the future, we end up in a difficult situation: if we have evidence now for the beliefs we will have why not have them now? And if we think that there is no evidence for those beliefs now, then how can we predict that we will be irrational?

Leaf Van Boven (University of Colorado Boulder) presented a talk entitled: “As the World Burns: Psychological Barriers to Addressing Climate Change and COVID—And How to Overcome Them”. His analysis is that the polarisation we see between liberals and conservatives does not come from deep ideological differences but from the thought that our political position represents who we are ("Party over Policy").

Van Boven's research shows that people do value policies in political decision making and when asked what their judgements should be based on, they respond that they think their judgements should be based on the policies. But in practice this does not happen and partly that's because the details of the policies are not accessible to the general public.

|

| Leaf Van Boven |

Experimental results show that policies receive better support from the public from all sides of the political spectrum when they are endorsed by nonpartisan experts and bipartisan coalitions of political leaders. This has implications for devising communication strategies that can reduce polarisation. But when elite politicians who are well-known to the public explicitly support some policies, polarisation increases and communication from elite politicians generates feelings of anger and divisiveness on controversial topics like climate change.

DAY 3

Lene Aarøe (Aarhus University) presented a talk entitled: “Do the facts matter? The power of single exemplars and statistical information to shape journalistic and politician preferences”. She started her talk by emphasising how using statistics in providing information to laypeople may not be effective. One reason is that in order to fully understand statistics, people need to have some skills. Another reason is that statistics may be dry and not attract enough attention.

Exemplars instead are simple to understand and very effective: one engaging story can do a lot to inform the public when used well. We have evolved in small social environments and our cognition is suited to the "intimate village" model. That is why exemplars work: the human mind has a built-in psychological bias to process information carried in exemplars.

|

| Lene Aarøe |

Social media are a particular apt means to deliver information and drive engagement via exemplars. Evidence suggests that exemplars make complex issues more understandable and interesting, trigger emotional involvements and increase political engagement. But there are also ethical and normative reasons to use exemplars: stories of ordinary people enable diverse representation of citizens and helps the media move aways from what the elites say. But there are problems too: exemplars cannot be easily generalised and may be the foundation for misperceptions and biased attitude formation. If some exemplars have negative consequences when extreme, why do journalists still use such exemplars?

Journalists prefer extreme exemplar (an exemplar that is characterised by a high degree of statistical or normative deviance from the issue to which it is connected). There are three possible explanations for this preference: (1) education, (2) psychological bias, (3) organisational context. Explanation one is that journalists are trained to value sensationalism as a ways to make news more vivid and concrete. Explanation two is that journalists like the rest of us prefer stories that are more unusual and interesting, stories that surprise us. Explanation three is that journalists need to justify their stories to their editors and some media pursue an attention-seeking strategy to maximise audience. Evidence points to the third explanation as the most convincing.

This suggests that media should be supported so that they are not seeking to increase audiences at the cost of objectivity in the news reported. But what can the public do? They can develop the capacity to regulate their emotions when they are exposed to extreme exemplars. One way to invite them to regulate their emotions and "resist the force of" the extreme examplar is to let them know about the psychological effects of exemplars.

Emily Vraga (University of Minnesota) presented a talk entitled: “What Can I Do? Applying News Literacy and Motivating Correction to Address Online Misinformation”. She reviewed solutions people have proposed on how to address misinformation on social media starting from literacy (what literacy though?

science literacy?

news literacy?). Literacy is about having knowledge and skills in a given domain. Each domain will determine which skills are needed. Which sources should I use? How can I verify content? How do I correct misinformation?

|

| Emily Vraga |

But literacy is very hard to build. It is expensive to teach and must be taught early on in schools. Most people who participate in public life are not in a classroom and needs to be updated all the time to be truly effective. Also, teaching literacy may bring critical thinking but may also lead to cynicism. One alternative is to provide quick tips, short messages, that people can use when they approach social media. But the tips that have been tried so far all seem to have mixed effectiveness. Intervention on social media are hard to make because people tend to ignore them.

Another solution is correction. Correction is when people respond to misinformation by providing correct information instead (give the facts); by describing why the techniques behind misinformation are misleading (question the method); by challenging the credibility of the source (question the motives). Correction can reduce misperceptions in the context of the misinformation. And on social media, even if the correction does not affect the person who spreads the misinformation, it affects everybody else who witnesses the interaction.

Studies have been conducted to measure the effects of observed correction in terms of reducing misperceptions: and the verdict is that it works. The message is: if you see misinformation, REACT!

Effective corrections are repeated (don't wait for someone else to correct); empathetic (respect other views); explanatory (don't just say "false" but explain what the truth is); credible (sources you use to correct are authoritative); timely (don't wait too long or people will have accepted misinformation as true).

- Repeat corrections

- Empathetic replies

- Alternative explanations

- Credible sources

- Timely response

Thanks to the Knowledge Resistance project for organising this amazing event!

|

| Group picture |