In this post, Kathleen reports on the public philosophy event, 'Values and Virtues for a Challenging World'. This was organised by Cardiff University in association with the Royal Institute of Philosophy. Academic philosophers had the chance to bring their work to the attention of public policy and education professionals and discuss the ideas. These ideas can now be read here in the latest issue of Royal Institute of Philosophy supplements (edited by Anneli Jefferson, Orestis Palermos, Panos Paris, and Jonathan Webber).

First up, was a panel with Sophie Grace Chappell and Panos Paris, chaired by Laura D'Olimpio. The topic was "Good Taste and the Experience of Value". Sophie Grace discussed the positive value found within the natural world, and that the appropriate response to this value is a sense of awe and beauty. We would do well to inculcate this virtue and continue to appreciate the beauty of nature, and this has a place in guiding policy on, for example, tackling climate change. Panos Paris talked about how our senses of beauty are often highly subjective, superficial, and not particularly related to our values. However, if we come to appreciate functional beauty, this can bring our tastes of beauty in line with our values. This is because functional beauty captures how well-formed something is for fulfilling its function.

|

| Panel 1 |

Next, was a panel with Alessandra Tanesini, Hugh Desmond and Taylor Matthews, chaired by Auriol Miller from the Institute of Welsh Affairs. The topic was "Polarisation, Mental Health and Misinformation on Social Media". Alessandra discussed how social media can facilitate mass contagion of group-based anger, and exacerbate simplistic emotional outlooks which reduce individuals to one specific group identity. This structural feature of social media is what ought to be changed about it. Hugh questioned the image of social media as a means to "care and share", suggesting that posting about our private lives often submits them to a status competition and this has knock-on effects for mental health. Finally, Taylor talked about the dangerous consequences of the proliferation of 'deepfake' videos. These are videos of people, often very well-known and important figures, which are completely faked and never happened. This is pushing us to distrust videos as a very valuable and trustworthy source of information, and now we need to cultivate 'digital sensibility' in assessing the credibility of videos.

|

| Panel 2 |

Next, was a panel with Lani Watson, Jonathan Webber and Kathleen Murphy-Hollies, chaired by Julian Baggini. The topic was "Curiosity, Integrity, and Self-Regulation". Lani talked about cultivating curiosity in a world full of easily accessible information and misinformation. The trick is to be appropriately motivated to pick out the lines of questioning and information worth knowing, and central to this will be asking good questions. Jonathan discussed the importance of ethical integrity, which is having an ongoing concern for consistently embodying our values across the very varied range of situations we come across. This will require balancing respect for existing ideas and values, with receptivity for new reasons for action. Kathleen discussed the phenomenon of political confabulation, which is when people unknowingly give false reasons for their political decisions after the fact. Instead of trying to stop confabulation ever happening, we should foster a virtue of self-regulation, which involves various skills used to align our behaviours better with our professed values. (Julian wrote a blog post discussing these ideas here).

|

| Panel 3 |

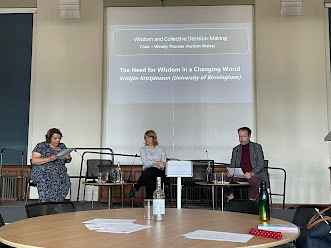

Next, was a panel with Kristján Kristjánsson and Anneli Jefferson, chaired by Wendy Thomas from Autism Wales. The topic was "Wisdom and Collective Decisions". Kristján recounted looking at which key terms were most used on social media throughout the pandemic, noting that there was a focus on single moral virtues such as resilience or compassion. The concept of wisdom was completely overlooked, when this is needed in a complex world in order to prioritise between competing moral demands and multiple relevant important virtues. Anneli discussed this notion of wisdom at not just the level of individuals, but of groups. Having a mix of cognitive styles in a group can help in making wise decisions. In particular, autistic people may have distinct advantages to bring; autistic people are often less susceptible to common biases, for example.

|

| Panel 4 |

Finally, the last panel was with Nadine Elzein and Mandi Astola, chaired by Catherine Fookes from Women's Equality Network. The topic was "Uncertainty and Polarisation". Nadine discussed the importance of the having 'interpretive charity' in this world, where social media algorithms push controversial content. This can mean that opponents are often caricatured and their views distorted, which only drives polarisation and misinterpretation. We should resist this ourselves and regulate social media to stop this happening. Mandi asked who we should blame for problems caused by a large group of people consisting of many individuals, and suggested that we should see the group itself as responsible. Furthermore, she suggested that group responsibility should be treated as a virtue and that groups ought to be well-organised in this way, otherwise they are responsible as a group for wrongdoings.

|

| Panel 5 |

Many thanks to the organisers and editors of the issue for putting the event together, and to the Royal Institute of Philosophy for helping fund this event.