In today's blog post, Mark Blagrove and Julia Lockheart present The Science and Art of Dreaming (Routledge 2023).

Mark Blagrove is Professor of Psychology and Director of the Sleep Laboratory at Swansea University. Julia Lockheart is Associate Professor at Swansea College of Art, University of Wales Trinity Saint David. They undertake public discussions and painting of dreams in the DreamsID.com science art collaboration.

Mark had become interested in investigating the memory sources of dreams through discussing individual dreams at length with the dreamer: this utilised the free association method of Sigmund Freud in which the putative mechanisms of dream formation during the night are followed back in reverse through free associations to the dream when awake.

This interest had resulted in studies that investigated gains of personal insight to the individual through the open-ended group discussion of dreams and their relationship to the recent waking life of the dreamer. In 2016, for the annual British Science Festival, Mark proposed holding public discussions of dreams, with a brief turn-up session for each dream sharer. He discussed this plan with artist Julia Lockhart who said that she could paint each dream as it was told and discussed, so that the dreamer would then be given an artwork which would act as a cue to future discussions of the dream with family and friends.

In recognition of Freud’s creation of the free association method each dream was painted onto pages torn, with publisher’s permission, from Freud’s book The Interpretation of Dreams. However, as the collaboration developed, with events in the UK, worldwide and online, it became clear that a different effect from the dreamer obtaining personal insights was also occurring. This was an increased understanding of the dreamer and the dreamer’s life circumstances in those with whom the dream was discussed, and hence an increased empathy towards the dream sharer. This resulted in experimental studies that showed increased state empathy towards dream sharers from those with whom the dream is discussed, and a significant relationship between trait empathy and frequency of dream sharing.

|

| Mark Blagrove |

The book describes the above development of the science art collaboration, and includes 22 dreams told to the authors and the corresponding painting for each dream. These paintings show how the dream can be returned to a visual form and the summary of each dream discussion shows how dreams can be related to the waking life experiences of the person; dreams were chosen where each had a specific relevance to the theme of a chapter. The book commences with seven chapters on the neuroscience and experimental psychology of dreams and dreaming. This includes the formation and recall of nightmares, the relationship of dream content to emotional waking life episodes, lucid dreams, and the brain basis of dreaming.

These chapters show that dreams are not a delirium but have quantifiable relationships with waking life experiences, concerns and conceptualisations. These relationships are further evidenced by a review and rereading of Freud’s famous case study of the young woman ‘Dora’. The case study is usually related as a criticism of Freud, in that Dora was subject to sexual harassment by a male friend of her father and Freud made diagnoses that she was indeed unconsciously in love with that man. Dora only saw Freud for 11 weeks and famously ended the psychoanalysis abruptly. But in that time she told two dreams to Freud and her free associations to the dreams, the book argues, show that the dreams were poignant depictions of the harassment and stressful family circumstances that were occurring to her. To give Freud credit, he recorded the dreams and Dora’s free associations and published them, and did believe that Dora was subject to ‘persecution’ by her father’s friend.

Given this clear meaningfulness of dreams, in that dreams can be related to the waking life circumstances of the dreamer, there have been many theories that hold that this indicates that dreaming has a function. In a chapter on theories of dreaming, the many such proposed functions are compared, for example, that in dreams we simulate physical or social threats to ourselves and practice overcoming those threats, that dreaming is the experience of memory consolidation during sleep, and may even have a role in that consolidation, and that dreams are an endogenous therapy for the reduction of fear memories, or for the processing of emotions in general from waking life.

Although there are many such hypotheses, the null hypothesis, that dreaming has no lasting effect on the mind or brain during sleep, is favourably explored. This is the epiphenomenal view, which holds that dreams are spandrels, an architectural and evolutionary term used to describe a functionless by-product. And so, for example, the dreams of key workers told to the authors in online sessions with worldwide audiences, which show relationships of the dream content to the stressful waking life experiences of the key workers, can be seen as epiphenomenal albeit meaningful products of the brain during sleep.

|

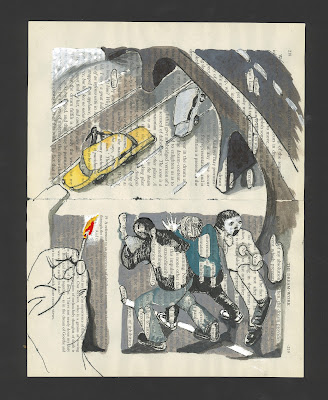

Dream of mother and daughter attacked on a Los Angeles freeway. Painting by Julia Lockheart, DreamsID.com |

In a sidestep, though, to the debate on whether dreaming has or does not have a function during sleep, the authors propose from their work on the eliciting of empathy as a result of dream sharing that dreams might have a post-sleep function of increasing empathy and bonding between people. They propose that in hominid history and in human prehistory dreams may have been more rudimentary than occurs for current human adults. This accords with Domhoff’s neurocognitive theory of dreaming, which holds that dreaming undertakes cognitive development from young children to young adults.

The authors propose that evolution may have selected for dream characteristics that elicit greater interest and empathic response from those with whom the dream is discussed. Dream content may thus have become subject to evolutionary selection on a timescale similar to the development of storytelling and group music making. They propose that dream sharing may thus have contributed to group bonding and human self-domestication, in which across human prehistory and history there has been decreased within-group aggression, inhibited emotional reactivity, and enhanced mentalising and empathy.