Today's post is by Stephen Gadsby. Stephen is a Fonds Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek (FWO) postdoctoral fellow, based at the Centre for Philosophical Psychology, Antwerp University. His research employs theoretical and empirical methods to explore a broad range of topics within philosophy, psychology, and psychiatry. These include eating disorders, delusions, self-deception, imposter syndrome, and body representation.

|

| Stephen Gadsby |

Sufferers of anorexia and bulimia often believe that their bodies are larger than reality. This appears undeniably irrational. Given that their bodies are not as large as they claim, such beliefs appear untethered to evidence. In my recent paper, I suggest that those who suffer from these disorders are not as irrational as they appear.

The first clue comes from first-person reports. These individuals often report experiencing changes in the physical size of their body, as if their stomach and legs were extended, expanding, or blown-up. Taking these reports at face value generates the question of how such illusory experiences could arise. The answer lies in a particular form of bodily awareness.

Close your eyes and focus on your body. That feeling of your bodily boundaries is your proprioceptive awareness. Proprioception helps us locate our bodies and navigate our environments, but it can also deceive us. For example, when you hit your thumb with a hammer and feel it enlarging.

Proprioception is facilitated by a mental map of the body called the body model. We experience our bodies as a certain size because this model represents us as that size. When the model changes, our experience of body size changes with it.

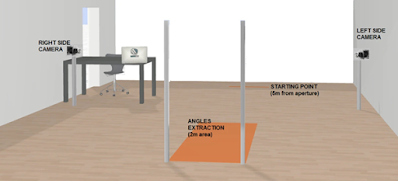

A clever way to measure the body model is by measuring how people move when navigating environments. Experiments using this method on participants with anorexia and bulimia find that their body models represent them as larger. For example, when walking through variously sized doorways, these participants turn their shoulders as if their bodies were wider.

The first clue comes from first-person reports. These individuals often report experiencing changes in the physical size of their body, as if their stomach and legs were extended, expanding, or blown-up. Taking these reports at face value generates the question of how such illusory experiences could arise. The answer lies in a particular form of bodily awareness.

Close your eyes and focus on your body. That feeling of your bodily boundaries is your proprioceptive awareness. Proprioception helps us locate our bodies and navigate our environments, but it can also deceive us. For example, when you hit your thumb with a hammer and feel it enlarging.

Proprioception is facilitated by a mental map of the body called the body model. We experience our bodies as a certain size because this model represents us as that size. When the model changes, our experience of body size changes with it.

A clever way to measure the body model is by measuring how people move when navigating environments. Experiments using this method on participants with anorexia and bulimia find that their body models represent them as larger. For example, when walking through variously sized doorways, these participants turn their shoulders as if their bodies were wider.

We know that many sufferers of anorexia and bulimia report experiencing their bodies as larger. We also know that the kind of dysfunction that would cause such an experience (an oversized body model) is associated with these disorders. Perhaps then, sufferers believe that their bodies are larger because they experience them that way, through proprioception.

There are a few features of this kind of misperception that are relevant to the question of rationality. Firstly, its persistence. Many sufferers report feeling this way every time they eat, see friends, or even all day long. Secondly, proprioception is a generally reliable source of information about the body. Contrary to appearances, then, sufferers of anorexia and bulimia do have evidence in support of their body size beliefs—a lot of evidence from a reliable source. Consequently, their beliefs are not as irrational as they appear.

Sufferer’s reports of proprioceptive misperception are often dismissed. As a result, attempts to convince them of their true size are unsuccessful. If we hope to change sufferers’ minds about their body size, I suggest, we must engage with the unsettling evidential circumstances that they find themselves in. We must focus on body model distortion and the proprioceptive misperception it induces.

There are a few features of this kind of misperception that are relevant to the question of rationality. Firstly, its persistence. Many sufferers report feeling this way every time they eat, see friends, or even all day long. Secondly, proprioception is a generally reliable source of information about the body. Contrary to appearances, then, sufferers of anorexia and bulimia do have evidence in support of their body size beliefs—a lot of evidence from a reliable source. Consequently, their beliefs are not as irrational as they appear.

Sufferer’s reports of proprioceptive misperception are often dismissed. As a result, attempts to convince them of their true size are unsuccessful. If we hope to change sufferers’ minds about their body size, I suggest, we must engage with the unsettling evidential circumstances that they find themselves in. We must focus on body model distortion and the proprioceptive misperception it induces.