Today's post is by Rosa Ritunnano (University of Birmingham). Rosa is a consultant psychiatrist and PhD candidate at the Institute for Mental Health. Here she talks about a recent paper she co-authored with an interdisciplinary group of international researchers at the Universities of York, Melbourne, Warwick and Ohio State. The paper entitled “Subjective experience and meaning of delusions in psychosis: systematic review and qualitative evidence synthesis” has been published in The Lancet Psychiatry and is available Open Access.

The aim of this research was to gain a deeper and more nuanced understanding of delusional phenomena based on the experiential knowledge of those with lived expertise—as the necessary basis for person-centred assessment and intervention. Here, we (attempted to) remain agnostic as to the nature of delusions (beliefs or other), conceiving of them as occurrent experiential states which have a specific phenomenology—that is, we assumed that there is a characteristic what-it-is-likeness to be in a certain delusional state and that this what-it-is-likeness can be investigated on its own terms. Our research question was: how do individuals with psychosis experience and make sense of changes in their self, world and meaning during the onset and progression of delusions?

For the first time, we reviewed all the available published qualitative literature in English that explored the lived experience of delusions in help-seeking individuals with psychosis, irrespective of diagnosis and thematic content of the delusion. In order to do this rigorously, we followed a particular methodology called “meta-synthesis” or “qualitative evidence synthesis”, which is widely used in the social sciences for integrating the findings of multiple primary qualitative research studies. This required screening 2115 references and then 133 full-text reports against pre-established inclusion criteria, until 24 eligible high-quality studies were left for inclusion in the final synthesis.

These 24 papers contained first-person accounts from 373 individuals with psychosis and lived experience of delusions, who were interviewed by the authors of the primary papers on different aspects of their delusional experiences. After importing all the findings into a data management software, we analysed the text through thematic synthesis, first coding it line by line and subsequently developing descriptive and then analytic themes to answer our research question. This method enabled us to stay “close” to the original words spoken by the participants, while at the same time moving beyond a simple aggregation of data and producing new hypotheses.

Three main analytic themes were generated from the thematic synthesis: 1) A radical, affectively charged rearrangement of the lived world dominated by intense emotions; 2) Doubting, losing, and finding oneself again within delusional realities; 3) Searching for meaning, belonging, and coherence beyond mere dysfunction (see figure below). In the paper, you can find a full discussion of themes and subthemes, and examples of the participants’ quotations supporting them.

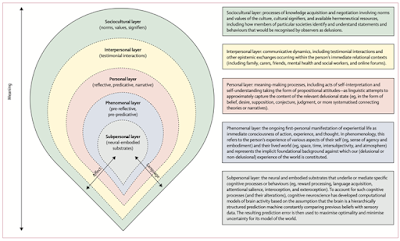

From these findings, we developed the “Emergence Model of Delusion” (figure below). This model suggests that delusions in psychosis are best understood as complex and multi-layered phenomena, emerging from a dynamical interaction between multiple processes happening at different levels of increasing organisational complexity (e.g., sub-personal, personal, inter-personal and socio-cultural). This in turns allows us to conceive of potentially dysfunctional mechanisms at one level, showing adaptive properties at a higher or lower level.

Notably, despite significant emotional and mental struggle, many participants described delusional experience as being accompanied by an enhanced sense of meaningfulness. This experience was interpreted by some in positive terms, albeit of short duration and often followed by a painful drop into depression and constant attempts at rebuilding self-trust. The role of interpersonal relationships appeared to be central in this process of building and rebuilding trust in self and others, both during and after the delusional period.

As a clinician myself, what I want to highlight here, is that all delusional experiences initiated a process of self-understanding and search for meaningfulness that appeared to clash painfully with the responses received by the participants from others (including mental health staff). These responses, mostly in line with a simple 'problem-solving' approach to remedying a dysfunction or a symptom of illness, could not help answering pressing existential questions such as “why is this happening to me?” or “what significance does it have?” For this reason, many described feeling alone and isolated.

Effective clinical care for individuals with psychosis might need adapting to match more closely, and take account of, the subjective experience and meaning of delusions as they are lived through by the person. Such an adaptation may also help redress power imbalances and enduring epistemic and hermeneutical injustices in mental health.

|

| Rosa Ritunnano |

This paper is the result of a big team effort, and my hope is that it will encourage delusion and psychosis researchers across disciplines to go beyond commonplace assumptions (deeply ingrained especially within clinical psychiatry) about the nature and meaning of delusional phenomena.

The aim of this research was to gain a deeper and more nuanced understanding of delusional phenomena based on the experiential knowledge of those with lived expertise—as the necessary basis for person-centred assessment and intervention. Here, we (attempted to) remain agnostic as to the nature of delusions (beliefs or other), conceiving of them as occurrent experiential states which have a specific phenomenology—that is, we assumed that there is a characteristic what-it-is-likeness to be in a certain delusional state and that this what-it-is-likeness can be investigated on its own terms. Our research question was: how do individuals with psychosis experience and make sense of changes in their self, world and meaning during the onset and progression of delusions?

For the first time, we reviewed all the available published qualitative literature in English that explored the lived experience of delusions in help-seeking individuals with psychosis, irrespective of diagnosis and thematic content of the delusion. In order to do this rigorously, we followed a particular methodology called “meta-synthesis” or “qualitative evidence synthesis”, which is widely used in the social sciences for integrating the findings of multiple primary qualitative research studies. This required screening 2115 references and then 133 full-text reports against pre-established inclusion criteria, until 24 eligible high-quality studies were left for inclusion in the final synthesis.

These 24 papers contained first-person accounts from 373 individuals with psychosis and lived experience of delusions, who were interviewed by the authors of the primary papers on different aspects of their delusional experiences. After importing all the findings into a data management software, we analysed the text through thematic synthesis, first coding it line by line and subsequently developing descriptive and then analytic themes to answer our research question. This method enabled us to stay “close” to the original words spoken by the participants, while at the same time moving beyond a simple aggregation of data and producing new hypotheses.

Three main analytic themes were generated from the thematic synthesis: 1) A radical, affectively charged rearrangement of the lived world dominated by intense emotions; 2) Doubting, losing, and finding oneself again within delusional realities; 3) Searching for meaning, belonging, and coherence beyond mere dysfunction (see figure below). In the paper, you can find a full discussion of themes and subthemes, and examples of the participants’ quotations supporting them.

Notably, despite significant emotional and mental struggle, many participants described delusional experience as being accompanied by an enhanced sense of meaningfulness. This experience was interpreted by some in positive terms, albeit of short duration and often followed by a painful drop into depression and constant attempts at rebuilding self-trust. The role of interpersonal relationships appeared to be central in this process of building and rebuilding trust in self and others, both during and after the delusional period.

As a clinician myself, what I want to highlight here, is that all delusional experiences initiated a process of self-understanding and search for meaningfulness that appeared to clash painfully with the responses received by the participants from others (including mental health staff). These responses, mostly in line with a simple 'problem-solving' approach to remedying a dysfunction or a symptom of illness, could not help answering pressing existential questions such as “why is this happening to me?” or “what significance does it have?” For this reason, many described feeling alone and isolated.

Effective clinical care for individuals with psychosis might need adapting to match more closely, and take account of, the subjective experience and meaning of delusions as they are lived through by the person. Such an adaptation may also help redress power imbalances and enduring epistemic and hermeneutical injustices in mental health.