This is the first in a series of posts reporting outcomes from a project on Agency in Youth Mental Health, led by Rose McCabe at City University. Today Joe Houlders, Matthew Broome and Lisa Bortolotti (University of Birmingham) talk about the risks of young people with unusual experiences and beliefs experiencing epistemic injustice in clinical encounters.

|

| Joe Houlders |

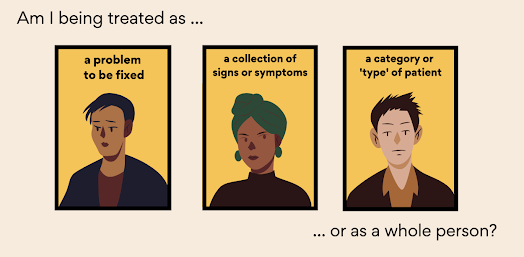

Epistemic injustice occurs when a person is not given authority and credibility as a knower in an exchange, due to negative stereotypes associated with the person's identity (age, gender, ethnicity, social class, education, sexual orientation, health). Young people with unusual experiences and beliefs are particularly at risk of being on the receiving end of epistemic injustice, and when their agency is undermined the effects are likely to be pervasive and impact negatively on their health outcomes.

Why is this population more vulnerable? In the mental health context, the manifestation of behaviours such as hearing voices and expressing paranoid beliefs can also lead to a person being silenced, dismissed, or denied agency. Without justification, perceived irrationality in one area of mental life (“In this context, this person cannot distinguish between imagination and reality”) is generalised to other areas of decision making and agency that may actually be unaffected by the person’s poor mental health.

What is the sense of agency and why does it matter? People have a sense of agency if they see themselves as the initiators of their actions; feel in control of their bodies and minds; and feel they can intervene on their environment. Young people may already be perceived as lacking agency. This is due to the common association in popular culture between youth and restlessness, unreliability, attention-seeking behaviour, laziness, recklessness, and lying. Examples would be the press’s use of the term “snowflakes” to refer to young people, and the assumption that young mothers are irresponsible and unable to take good care of themselves and their children.

Why is it important to protect a young person's sense of agency in clinical encounters? We know that shared decision-making and empowerment are linked to good therapeutic relationships and better clinical outcomes. If young people are unable to contribute to the decision-making process because they are silenced or feel powerless, then the quality of their therapeutic relationships with medical professionals and their clinical outcomes may be compromised.

Moreover, the identity of young people in general is still fluid and more likely to be shaped by social interactions with power imbalances—the effects of challenging the sense of agency of a young person may be more pervasive than the effects of challenging the sense of agency of a person whose identity is more securely established. In the words of a member of the Youth Project Advisory Group in our project:

Further, the sense of agency of people with unusual experiences and beliefs may be more precarious to start with, due to the fact that unusual experiences and beliefs often undermine the sense of oneself as someone capable, efficacious, and in control. Young people with such experiences and beliefs may be more inclined to question themselves.

So far, we only mention possible risks for epistemic agency, but we also have evidence that people with psychotic symptoms are dismissed in conversations during clinical encounters, and their capacity for producing and sharing knowledge is undermined by the healthcare practitioners' attitudes.

[Patients with psychotic symptoms] clearly attempted to discuss their psychotic symptoms and actively sought information during the consultation about the nature of these experiences and their illness. When patients attempted to present their psychotic symptoms as a topic of conversation, the doctors hesitated and avoided answering the patients' questions, indicating reluctance to engage with these concerns. (McCabe et al. 2002, p. 1150)

If you want to know more about the risks of epistemic injustice for young people struggling with their mental health, you can read our paper (published in Synthese in 2021, open access).

You can also follow the other posts in this week's series: tomorrow Clara Bergen and Rose McCabe will discuss more evidence of epistemic injustice in clinical encounters; on Thursday, Clara Bergen and Lisa Bortolotti will present some findings leading to concrete suggestions about what practitioners can do to protect young people's sense of agency; on Friday, Rachel Temple and the members of the project's Young Person Advisory Group will talk about the significance of the project for them.