On Thursday 13 April 2017, a workshop organized at Columbia University by the Centre for Science and Society and the Italian Academy for Advanced Studies in America sought to explore an important and still partly unresolved question: How does our brain make sense of scents and flavors?

Importantly, a key goal of the exploration was to debunk some myths about the human sense of smell. Most notably, it targeted the view that our olfactory abilities are underdeveloped and lack cognitive significance. An eminent advocate of this proposition was Immanuel Kant, who wrote the following:

Quite often, reasons given for thinking that we do not experience smells all the time include our supposedly poor sense of smell. Many say that they hardly notice their sense of smell and imagine it would be easy to give it up if they had to lose one of their senses. Yet, on Smith’s view, we can think of olfactory experience as a background to consciousness: part of the fabric that we no longer pay attention to until it changes dramatically. In that background role, smells can modulate our moods, and condition our responses. Smell is always with us: we smell because we breathe and we live in a world full of odors that subtly shapes our moods, influences our eating habits, our choice of partner, our recognition of kin, and our response to one another’s fear or aggression. Given this wide role that olfactory system plays in the conscious experiences of daily life, it is surprising that we typically pay so little attention to smell.

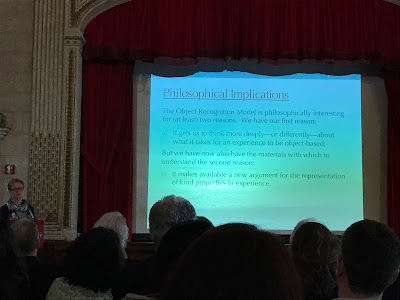

Another important philosophical contribution was by Clare Batty, who addressed the questions of whether and how human olfactory experience represents objects. In much of the philosophical literature on perception, there is the implicit assumption that vision is the paradigmatic sense modality, and that the visual case provides a basis for conclusions about the other modalities. Whilst philosophers have recently begun to correct this assumption by considering other modalities, relatively little has been written about olfaction. As it turns out, it is commonplace to hold that visual experience represents objects. After all, visual experience displays a rich form of perceptual organization that allows us to think and speak of individual apples and oranges, or particular cats and dogs. Olfactory experience seems to lack such organization, and if we take this organization as necessary for the representation of objects, we are then led to believe that olfactory experience does not represent objects. Still, Batty suggested that olfactory experience does indeed represent objects, although not in a way that is easily read from the dominant visual case.

Yet philosophy was not the only perspective represented at the workshop. In particular, Donald Wilson offered plenty of insights into the current status of the science of olfaction. Many important lessons were delivered. He explained, for instance, how humans actually have very sophisticated palate, much more than many other animals, and we know that most of flavor is really olfaction. He also showed how complicated olfaction actually is. We do not have for most of odors a receptor for that particular odor: we do not have a coffee receptor or a vanilla or a strawberry receptor. We have receptors that are recognizing small pieces of the molecules that we are inhaling, and the aroma of coffee, for example, is made up of hundreds of different molecules. So what the brain then has to do is make sense of this pattern of input that is coming in. And what the brain is doing with the olfactory cortex and the early parts of the olfactory system are doing is letting those features into what we and others would consider something like an odor object, so that we perceive now a coffee aroma from all of these individual features that we have inhaled.

Finally, the workshop also sought to bring in perspectives from perfumers and entrepreneurs, i.e. Avery Gilbert and Christophe Laudamiel, stressing how smells have also come to shape our modern socio-economic landscape and how today billions of dollars are generated annually with fragrance products in the US alone.

Importantly, a key goal of the exploration was to debunk some myths about the human sense of smell. Most notably, it targeted the view that our olfactory abilities are underdeveloped and lack cognitive significance. An eminent advocate of this proposition was Immanuel Kant, who wrote the following:

"Which organic sense is the most ungrateful and also seems to be the most dispensable? The sense of smell. It does not pay to cultivate it or refine it at all in order to enjoy; for there are more disgusting objects than pleasant ones (especially in crowded places), and even when we come across something fragrant, the pleasure coming from the sense of smell is always fleeting and transient" (2006 [1798], 50-51)The panel sought to bring together different perspectives to show how this view turns out to be incorrect and to investigate the human sense of smell in its many dimensions and from different angles. After some introductory remarks by David Freedberg, Pamela Smith, and by Ann-Sophie Barwich (who will present her new research on this blog in the next few weeks), it was philosopher Barry Smith who started by addressing the role of the sense of smell in perception and conscious experience.

Quite often, reasons given for thinking that we do not experience smells all the time include our supposedly poor sense of smell. Many say that they hardly notice their sense of smell and imagine it would be easy to give it up if they had to lose one of their senses. Yet, on Smith’s view, we can think of olfactory experience as a background to consciousness: part of the fabric that we no longer pay attention to until it changes dramatically. In that background role, smells can modulate our moods, and condition our responses. Smell is always with us: we smell because we breathe and we live in a world full of odors that subtly shapes our moods, influences our eating habits, our choice of partner, our recognition of kin, and our response to one another’s fear or aggression. Given this wide role that olfactory system plays in the conscious experiences of daily life, it is surprising that we typically pay so little attention to smell.

Another important philosophical contribution was by Clare Batty, who addressed the questions of whether and how human olfactory experience represents objects. In much of the philosophical literature on perception, there is the implicit assumption that vision is the paradigmatic sense modality, and that the visual case provides a basis for conclusions about the other modalities. Whilst philosophers have recently begun to correct this assumption by considering other modalities, relatively little has been written about olfaction. As it turns out, it is commonplace to hold that visual experience represents objects. After all, visual experience displays a rich form of perceptual organization that allows us to think and speak of individual apples and oranges, or particular cats and dogs. Olfactory experience seems to lack such organization, and if we take this organization as necessary for the representation of objects, we are then led to believe that olfactory experience does not represent objects. Still, Batty suggested that olfactory experience does indeed represent objects, although not in a way that is easily read from the dominant visual case.

Yet philosophy was not the only perspective represented at the workshop. In particular, Donald Wilson offered plenty of insights into the current status of the science of olfaction. Many important lessons were delivered. He explained, for instance, how humans actually have very sophisticated palate, much more than many other animals, and we know that most of flavor is really olfaction. He also showed how complicated olfaction actually is. We do not have for most of odors a receptor for that particular odor: we do not have a coffee receptor or a vanilla or a strawberry receptor. We have receptors that are recognizing small pieces of the molecules that we are inhaling, and the aroma of coffee, for example, is made up of hundreds of different molecules. So what the brain then has to do is make sense of this pattern of input that is coming in. And what the brain is doing with the olfactory cortex and the early parts of the olfactory system are doing is letting those features into what we and others would consider something like an odor object, so that we perceive now a coffee aroma from all of these individual features that we have inhaled.

Finally, the workshop also sought to bring in perspectives from perfumers and entrepreneurs, i.e. Avery Gilbert and Christophe Laudamiel, stressing how smells have also come to shape our modern socio-economic landscape and how today billions of dollars are generated annually with fragrance products in the US alone.